Of the many various methods of recording, one has stayed, relatively speaking, under the radar: Binaural recording. But what is it? Binaural recording is basically the technique used to create very realistic, or 3-D, sound recordings. When these are listened to, extremely realistic playback is heard, and it’s truly like the listener is in the scene of the recording.

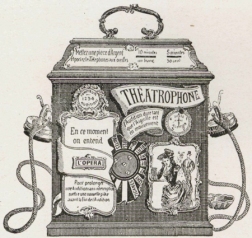

Binaural recording has its roots back in the late 1800’s in the form of a device called a théâtrophone.

It looks like this:

These devices used telephone lines to send audio from operas and other such events to the listener. The two separate receivers created a rudimentary binaural recording. Of course, the quality was poor, but time would eventually change that.

The next eventual step found itself in the form of of Oscar. Oscar was a 1933 human like fake head created by AT&T. It debut at the Chicago World Fair. It had tow microphones for ears and was even closer to a modern day binaural recording. However, it wasn’t perfect either. So, what came after Oscar? A more sophisticated Oscar. However, AT&T didn’t craft the 1972 binaural head, but it was instead Nuemann, a company known for microphones. It was called the KU-80, and it’s the predecessor to the KU-100, the modern day binaural recording dummy head that goes for $8000.

A KU-100: (http://www.coutant.org/ku100/ku100.jpg)

So, how does it work? Acoustics and two microphones is the short answer. Now then. if you were to set up two plain old microphones on a room and create noise all around them, you’d find that the recording doesn’t sound like all it’s cracked up to be. Well, that’s because you’re doing it wrong. The reason the head is used is because of the way it interacts with sound, and this interaction is what makes the binaural recording so realistic. You may not realize this, but our head and ears greatly shape what we hear. There are two main components to this: head shadow and the pinna.

Imagine you’re looking down at an ocean shore, and let’s say you see a giant rock in the water. Now, as you watched waves propagate from the ocean, you’d see them bend around the rock, bounce of it, etc. This is what happens with head shadow. Our heads, the rock, cause sound, the waves, to move around and bounce of it. But the head also absorbs high frequency sound as well, and lower frequencies actually bend around it. Now, if the sound hits the side of your head, it will first enter your ear, but at the same time, some of it bends around you and enters your other ear. Our brains can sense the difference in time between sound entering one ear over another, and this is a crucial part in replicating a realistic recording: it helps dictate direction and location.

Now, if you take another look at the KU-100, you see that the head is actually pretty simple, but the ears are very detailed. Why? Those parts of our ears, called the pinna, drastically change what we’re hearing, and tell is where sound is coming from in another way. The first thing the pinna do is collect sound, making our hearing more efficient, but they do something else too. Take a look at this graph, called a Fletcher-Munson curve: (http://www.nonoise.org/library/animals/5.gif)

You’d think that we hear things all the same, right? Wrong. That is how we hear, and as you can see, for example, at the point where you can just barely hear the frequency of 4kHz, a 20 Hz sound has to be around 70dB louder, just to hear it! That’s a lot. In fact, the quietest level of sound most people hear on a daily basis is around 30-40dB. Our ears mold sound to be no where near what it actually is. But this isn’t bad, because, in short, it also creates comb filtering. Comb filtering are various notches in sound (typically caused by phase difference, or the time difference between 2 or more sounds). It kind of looks like this: (http://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fx_files/35228/1/comb.jpg)

As you can see, this isn’t flat either.

Here’s what it sounds like:

(Fun Fact: if you have sound coming out to speakers, like usual, giving the right positioning, you can actually create this naturally. Try moving around in front of the speakers (not too close, though), and if you do it right, you’ll hear that flange, comb filtered sound being produced like in the video.)

So why is all this changing of sound important? Also, you’d think all this sounds like what we hear should be horrid. Well, in short, it’s all helpful for us (We’ve all grown up listening like this, so it sound natural). Our ears use this comb filtering effect to tell use if a sound is above or below us.

So, combining all this acoustic stuff, the head and ears give us our 3-D perception of sound. (Now, try snapping or clapping in front, behind, above, and below your head). That head used for a binaural recording does the same thing: it’s like a real human listening.

But as you may recall, it’s not all acoustics, because the second ingredient in these things are two microphones. It’s pretty easy to figure out where the microphones are located: it’s where our ear drums normally would be. This makes sure that the microphones pick up all the sound and all those acoustic effects. However, the microphones themselves need to be flat, because you don’t what them to boost or cut anything, as this could ruin the effect if it’s severe enough. The mics also need to be omnidirectional, meaning they record sound evenly in all directions.

To sum this up, put everything together, and you’ll get a binaural recording because the head is shaping the sound exactly like our heads do. This captures all the effects that make 3-D sound.

OK, great, you’ve recording something. How do you play it back? Well, the best way to hear a binaural recording is though some headphones or ear buds. If you attempt to listen to it through speakers, the illusion will be destroyed. This is because you’ll hear the sound from both speakers entering each ear. This is not how the sound needs to be played back. You see, with headphones, the left channel only enters the left ear, and the right channel only enters the right ear. Naturally enough, our right ear doesn’t hear what the left ear hears and vice versa, so when listening, the ears can’t hear both channels. Headphones do this (Theoretically, you could do this with speakers, so long at the right speaker only is heard by the right ear and the left speaker is only heard by the left ear, but that could be expensive and difficult. This is actually a thing called stereo dipole, a type of speaker placement, that removes crosstalk pretty well. Look it up for more info).

Finally, here are some examples of binaural recording.

The first one is a live music performance. First, it’s in mono for about a minute for comparison purposes, then it goes binaural. Second, I would recommend closing your eyes and picturing the image it creates, and don’t forget to where some headphones:

Here’s a virtual haircut using binaural recording. Close your eyes:

Try this too:

Beautiful, yes? I’m sure some of you are asking this: Can I try this at home? Well, technically, yes, if you have the money. Binaural recording doesn’t need some special, magic environment to work, so it’ll work anywhere. But if you want to use the KU-100 for the best sound, $8000 will be needed, but I’m going to assume you don’t have that kind of money for a fake head. Fear not, for there are alternatives.

There’s a microphone technique called the MS technique. Read more on that here: http://www.uaudio.com/blog/mid-side-mic-recording/

The second option is using microphone ear buds, like the Roland CS10EM. These are much more affordable. They are ear buds that you stick in your ears and have playback, but they also each have a mic inside. Do they work as well as the dummy head? No, as the acoustical properties the head and ears make are partially removed, because the mics on the outside of the ear piece.

I’m also sure that the Nuemann head and other expensive similar products can be rented.

But what do I think about all this? It’s awesome, in short. I could easily see this thing being used for movies/video, virtual reality video games, and live performances. And seeing as you only need headphones or ear buds to make this work, the possibility of it breaking heavily into the market is high. However, when it comes to using this for most popular music that utilizes multitrack, it’s possible, but tricky. The head would need to remain in the same place for consistency, and adding any close mics, to drums for example, could ruin the image it creates. Modern production techniques will have to change somewhere for it to work, but who knows what the future will bring. Let’s see where it goes.

Some sources